Text: Lydia Kalda

Photos: Museum of the Coastal Swedes

The small Museum of the Coastal Swedes on the shores of Haapsalu’s picturesque Tagalaht bay preserves the rich history of the Estonian Swedes, presented by Göran Hoppe, professor of cultural geography at Uppsala University.

Estonia was home to a strong community of Estonian Swedes with their own language and culture. It began a few thousand years ago with shipbuilders and sailors who settled here and learned how to farm, fish and hunt.

The Estonian Swedes lived on the north-west coast of mainland Estonia from Haapsalu to Kurkse, and on the islands of Naissaare, Suur- and Väike-Pakri, Osmussaare, Vormsi, Hiiumaa and Ruhnu. These regions were collectively known as Aiboland, which translates to “the lands of the islanders”. They spoke Swedish, but each locality had its own dialect akin to a secret language, incomprehensible to foreigners. Linguists believe that the dialects of the Estonian Swedes originate from southern Sweden: the coast of Kalmar, Öland, Gotland, Östergötland. Archaeological excavations would give a more precise answer.

Embroidered history

For over 20 years now the museum has hosted a gathering of the Thursday Nans every Thursday, all of whom have Estonian Swedish roots. They pass on crafting traditions and recount their stories and memories to visitors. The nans have etched themselves into history with the most famous exhibit at the Museum of the Coastal Swedes, a 20-metre tapestry known as Rannavaip, which depicts the long history of the Estonian Swedes and interesting facts about their habitat, all embroidered with love and care. The tapestry has adorned the museum since 2002, when the Swedish royal couple opened the museum in Haapsalu.

Swedish law

Unlike Estonians, the Swedes were not serfs. Swedish law, established by the Swedish rulers, protected them and their rights. They were not required to work for manor lords, but could pay taxes in grain, meat, leather and furs, cheese, dried or salted fish, etc. The privileges aroused strong opposition from the local lords, but the Swedes did not give in. One of the most tragic episodes in their history was the deportation of thousands of Swedes from Hiiumaa to Ukraine in 1781.

Bread and butter of Estonian Swedes

For centuries, Estonian Swedes were known for their mastery of building wooden boats. This craftsmanship was passed down from generation to generation. Each island had different kinds of boats. Some ship models are displayed in the museum, which studies and even builds the traditional wooden boats used by Estonian Swedes. Their largest example is currently the Ruhnu yawl.

The Estonian Swedes mostly made their living from the sea. The people of Osmussaare hunted waterfowl and sealing played an important role on all the islands. At the same time, they also raised livestock. Compared to Estonians, the Estonian Swedes had large herds of pigs, cows, sheep and goats. They kept poultry and were skilled cheese makers. Even though the rocky soil made farming difficult, they still managed to grow barley, rye, swedes and later potatoes. On top of that, the Estonian Swedes were skilled craftsmen, making everything from clothes to guns with their own resources. As able seafarers, they visited Finland and Sweden for trading.

Music echoes across the land

The Estonian Swedes brought their own culture with them and each region wore its own costume. There were various societies dedicated to music, singing and plays that helped to preserve local traditions and folk dances. Various instruments were played. The talharpa was a beloved instrument on Vormsi already in the Middle Ages – every man knew how to build and play one. Unfortunately, the talharpa was ostracised in the turmoil of history and forgotten for more than a century. From the early days, bagpipes were played on the Pakri islands, while the violin and melodeon were more common in Noarootsi.

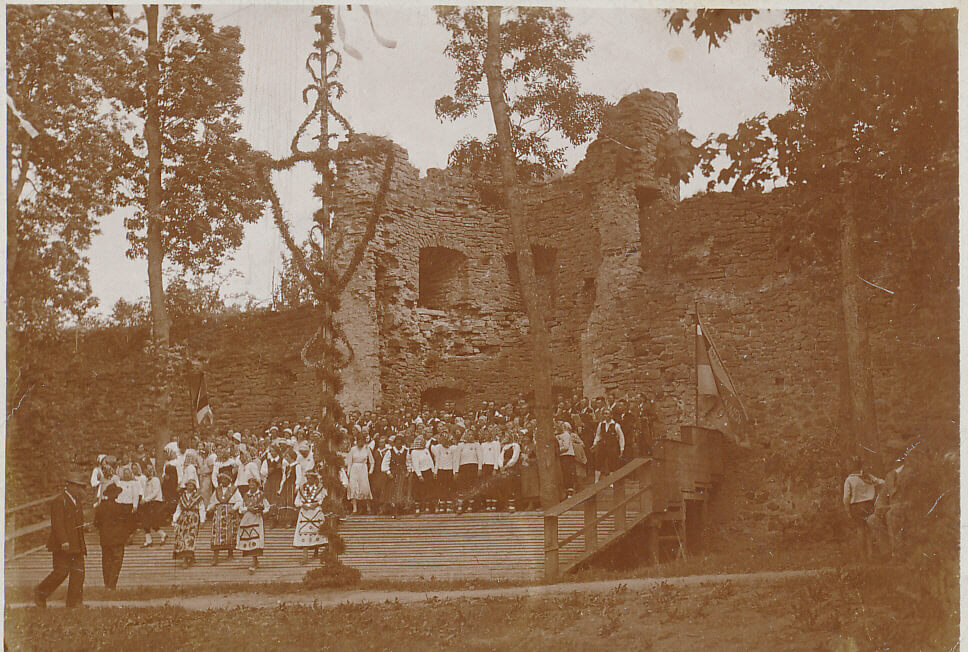

The Estonian Swedes have their own song and dance festival tradition. The first such festival was held in 1933 in Haapsalu Castle and its art director was the composer Cyrillus Kreek. It was impossible to practise local cultural traditions during the Soviet era, as national identity was suppressed. When Estonia regained its independence, the Estonian Swedes were also freed from the occupying forces. Haapsalu Castle hosted the second song and dance festival of the Estonian Swedes in 2013, as well as the fourth one on 27 June 2020.

The Museum of the Coastal Swedes celebrates traditional music, organises events and concerts, and researches and preserves musical heritage. People are keen to learn to play the talharpa.

Education and enlightenment

The Estonian Swedes were Lutherans whose culture and development was strongly influenced by clerics and missionaries from Sweden and Finland who came here to teach them. Services were held in Swedish.

At the same time, the Estonian Swedes played an important role as pioneers of local school education. Bengt Gottfried Forselius, the son of a Swedish priest, was the founder of Estonian folk education. He opened the first folk school in 1683 in the barn-dwelling near Risti clergy house. The Paslepa Teachers’ Seminar was set up to train teachers for the schools in Estonian Swedish villages. The Estonian Swedes had their own agricultural school in Pürksi manor in Noarootsi and a special Swedish-language private upper secondary school in Haapsalu, with teachers recruited from Sweden and Finland. Teaching took place in standard Swedish, causing local dialects to gradually disappear.

In 1909, the Estonian Swedes founded the Svenska Odlingens Vänner (Friends of Swedish Education), which is still active in Stockholm. Since 1918, the society has published the magazine Kustbon or Randlane.

Estonian Swedes carry on

The village names on Vormsi are Swedish to this day and visitors to Noarootsi are greeted by signs in both Swedish and Estonian. The Swedes had a Swedish name for each place, which was different from the Estonian name. For example, Swedes call Hiiumaa Dagö, Vormsi Ormsö, Ruhnu Runö, Noarootsi Nuckö, with islands marked by the letter ‘ö’ in Swedish. However, the suffix ‘-by’ in place names refers to a village.

Estonian Swedes are united by several associations and societies in their home area. They even publish their own magazines. The preservation of the language and culture of the Swedish national minority is protected by the Estonian-Swedish Cultural Government (Eestirootslaste Kultuuriomavalitsus). More than 500 people are on the nationality list of national minorities, continuing the tradition of Swedishness in Estonia. Several books have been published on the cultural history of the Estonian Swedes. Among the most prominent works is Carl Russwurm’s ‘Eibofolke oder die Schweden an den Küsten Ehstlands und auf Runö’ (title in English: ‘Eibofolke or The Swedes On the Coast of Estonia and Ruhnu’) which was first published in German in 1855. There are numerous other publications that also provide a good insight, such as ‘Raamat Eestimaa rootslastest’ (title in English: ‘A Book about the Swedes of Estonia’), ‘Kuldrannake’ (original title in Swedish: ‘Guldstrand’, English title: ‘Golden Beach’) and ‘Hans Pöhl’.

You can learn more about the life and culture of the Estonian Swedes in the Museum of the Coastal Swedes in Haapsalu, Sadama 32 or at www.aiboland.ee. The museum has a branch on the island of Ruhnu, in the Korsi Farm longhouse with a curved roof, one of the last surviving complete Ruhnu-Swedish farm complexes in the world.

History on a loom

The embroidered tapestry in the Museum of the Coastal Swedes tells the history of the Estonian Swedes up to World War II, which scattered a once strong community across two sides of the Baltic Sea. Around 7000 Estonian Swedes fled to Sweden while those who stayed in Estonia had to suppress their national identity. The follow-up tapestry currently being embroidered records life in both Estonia and Sweden after the 1940s. Life goes on!